Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1930 – The big trial had just ended. Judge Manuel Rodriguez Ocampo convicted 108 criminals with long sentences, forever disrupting the activities of the Zwi Migdal, the 30-year old, Jewish-run, most profitable prostitution ring in South America and beyond. It was a victory for many, but above all for the woman who, by testifying, had made this trial possible: Raquel Liberman.

Liberman, like many other women, had suffered by the hands of the Zwi Migdal, a Jewish criminal organization which, under the façade of a mutual aid organization, ran an Argentina-based profitable brothel business between the 1860s and 1930. Its members deceived young and impoverished Jewish women in Eastern Europe and, under the false pretense of a marriage, would whisk them away to South America, where they would be exploited as sex workers.

At a time where prostitution was not a crime in Argentina and many of the immigrants were men with no family in the country, the business of brothels was indeed a thriving one, recounted Nora Glickman, professor of Spanish at Queens College New York, in a book on the subject. One of its biggest players was the Zwi Migdal, founded in 1906 and named after its founding member, Luis Zvi Migdal.

By 1929, the Zwi Migdal was believed to be constituted by around 500 pimps, it controlled 2,000 brothels and employed 30,000 women, according to the late writer Ernesto Goldar. Headquartered in Buenos Aires, but with offices also in Brazil, South Africa, India and China and Poland, the organization had revenues amounting to approximately $50 million per year, according to Canadian journalist Isabel Vincent.

A contemporary described the Zwi Migdal as “an octopus, achieving an almost unassailable position,” reported Vincent in her book on the criminal association.

The story of Raquel Liberman

Liberman was only 22 years old, when she arrived at the port of Buenos Aires in 1922, according to her biography in the Jewish Women’s Archive. Liberman had come from Poland with her two very young sons to join her husband Yaacov Ferber, who had travelled to South America a year before. Only a couple of months later, Liberman found herself a widow, as Ferber had died from tuberculosis.

Having to support her children and with no knowledge of Spanish, Liberman thought her only hope laid in the Jewish merchants of Buenos Aires. She left the small village of Tapaquè, where her husband’s family had settled, and returned to the capital. But while the Liberman thought she would have worked as a seamstress, as she had done back home, she instead became a prostitute. Years later, her occupation made her cross paths with the Zwi Migdal and its trafficking activities.

Unlike in Liberman’s case, traditionally the operations of the Zwi Migdal would begin in Europe. Jewish pimps would approach young girls from impoverished families in Eastern European cities and rural areas. They would introduce themselves as wealthy businessmen and tell the girls’ families they were looking for a bride or for a young woman to join their domestic staff, reported Vincent, the Canadian journalist. Parents gave their daughters away thinking they were setting them up for a brighter future. In reality, they were signing them off to prostitution.

Sophia Chamys, 13, lived in a shtetl outside Warsaw at the end of the 19th century, when she met Isaac Boorosky at Castle Square, recounted Vincent in her book. He said he was looking for a girl to help out in his mother’s household. Boorosky was in reality a member of the Zwi Migdal. Chamys’s parents let her go, feeling even better about their daughter’s prospects once Boorosky said he wanted to marry Chamys and organized a rushed, unofficial wedding, with the pretense that he had to immediately leave for business to South America with his new wife.

Chamys died at only 18, having spent her last five years as a prostitute between Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro and Poland, under the strict control of Boorosky or one of his ‘business associates’.

When Liberman started out as a prostitute in Buenos Aires, she had a much better standing than Chamys. Liberman had to give only a percentage of her earnings to her pimp, Jaime Cissinger, in exchange for protection, said Glickman. In 1927, when Liberman had earned enough to buy her freedom, she opened an antique shop on Avenida Callao, one of the very long streets today still vertically crossing Buenos Aires.

A little later, Liberman married Josè Salomon Korn at the synagogue on Avenida Cordoba. The young woman didn’t know it back then, but that building was the central office of the Zwi Migdal and Korn was one of its pimps. Her marriage was a farce.

Soon after becoming Mrs. Korn, Liberman was sent by her own husband to work again in a brothel. Korn was not only exploiting her, but many other women, recounted Glickman. Liberman asked for help to another Jewish businessman she knew, Simon Brutkievich, recounted Glickman, not knowing Brutkievich was actually Zwi Migdal’s president. Liberman had no choice but to look for outside help.

At the time, resistance against the Zwi Migdal was spread in the local Jewish community in the form of associations, keen to establish a distance between themselves and the ‘impure’ pimps, practicing a trade which threatened the Jewish moral system. Amongst them, were the Soprimitis and the Ezrat Nashim, remembered Glickman. The former provided help to Jewish immigrants in Argentina on how to fight the impure, while the latter operated in the port of Buenos Aires and tipped off young women travelling alone on the risks of getting involved with pimps.

The final verdict

But none of these associations could help Liberman, better than the authorities. On New Year’s Eve of 1929, the woman came before Julio Algasaray, deputy commissioner of the police of Buenos Aires, to tell her story and become an informant, says Glickman. Algasaray had been waiting for someone to come forward for years, while gathering information and evidence on the criminal organization. The moment for a trial had finally come.

434 members of the Zwi Migdal were called before justice and judge Rodriguez Ocampo. Only 108 were convicted, said Glickman, but this trial was a turning point for the Zwi Migdal as brothels began to close and pimps to be deported and incarcerated.

The legal battle against the Zwi Migdal, which had corrupted many officials in the Argentinian capital, felt to Algasaray as a face-off between “a Lilliputian against Hercules,” as he said in one exposè written later.

Several of the Zwi Migdal pimps managed to flee to neighboring countries like Uruguay and Brazil, avoiding any form of punishment, wrote Glickman.

As for Liberman, she had little time to rejoice. She also never returned home to Poland, as she had intended to. On April 7th 1935 around 1 PM, she died of thyroid cancer at the Argerich Hospital in Buenos Aires, revealed her death certificate. The Zwi Migdal had turned Argentina, a land where she had dreamt of living happily ever after with her first husband, into a nightmare of prostitution and exploitation.

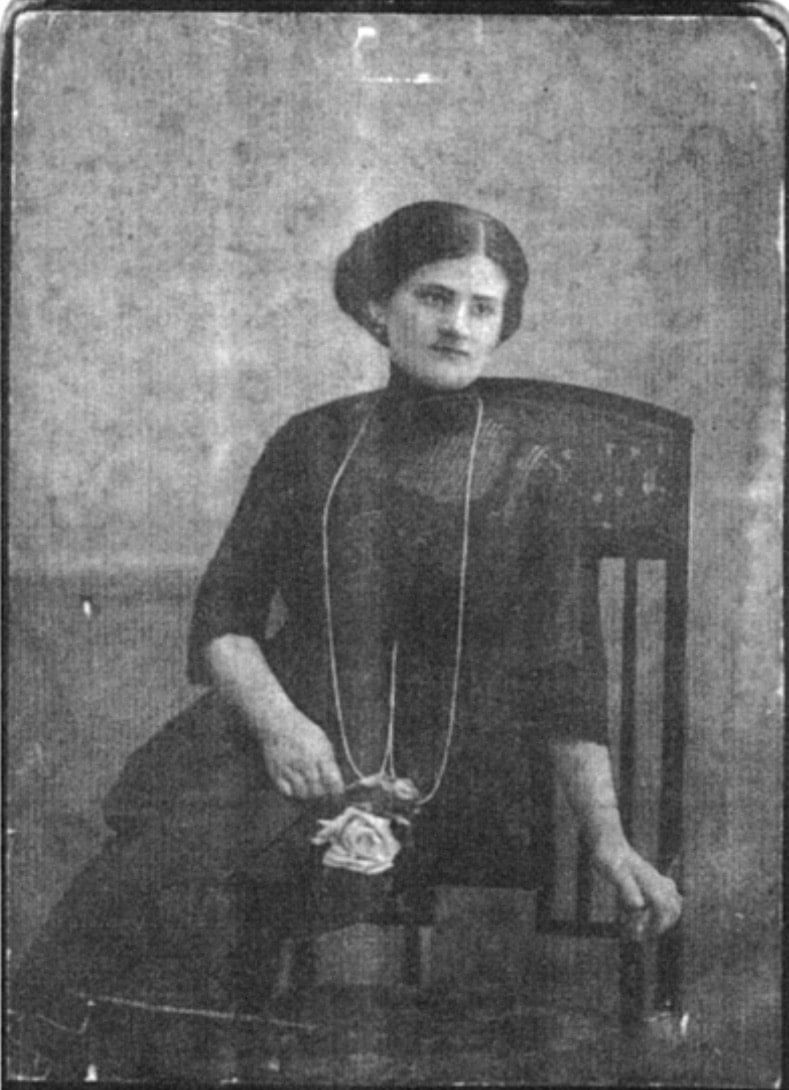

Page of a Buenos Aires’s daily, Diario Critica, after the verdict against the Zwi Migdal, 1930 (Credit: Diario Critica)

Bravo ragazza!!! non parliamo di queste cose . . . . . .

What a disgusting practice. 30,000 girls and women! I’m glad the world is paying more attention to these sort of abuses. Hopefully if the public is made aware enough then justice can be done, no matter who is bribed.